Insights

A model approach to museums.

Creating the conservation environment.

A three-part insight series: part 2

In part one I explored how museum design relies on the careful balance of user expectation and the environmental requirements for conservation. But just how do we go about achieving this?

One of the first considerations is the building itself. Often museums and galleries are housed in historic buildings, so understanding the structure and its heritage is vital.

In some cases, these buildings are as important as the objects displayed or stored within.

Working with the wider project team to undertake a process of industrial archaeology can reveal how the building was originally constructed and designed to operate in environmental terms. Often the originally intended climate-control strategies (such as natural ventilation, thermal mass, form and orientation) provide a valuable route to achieving the required environmental conditions with minimal interventions. Working with, and celebrating, these structures can also add a valuable dimension to the completed project as a whole.

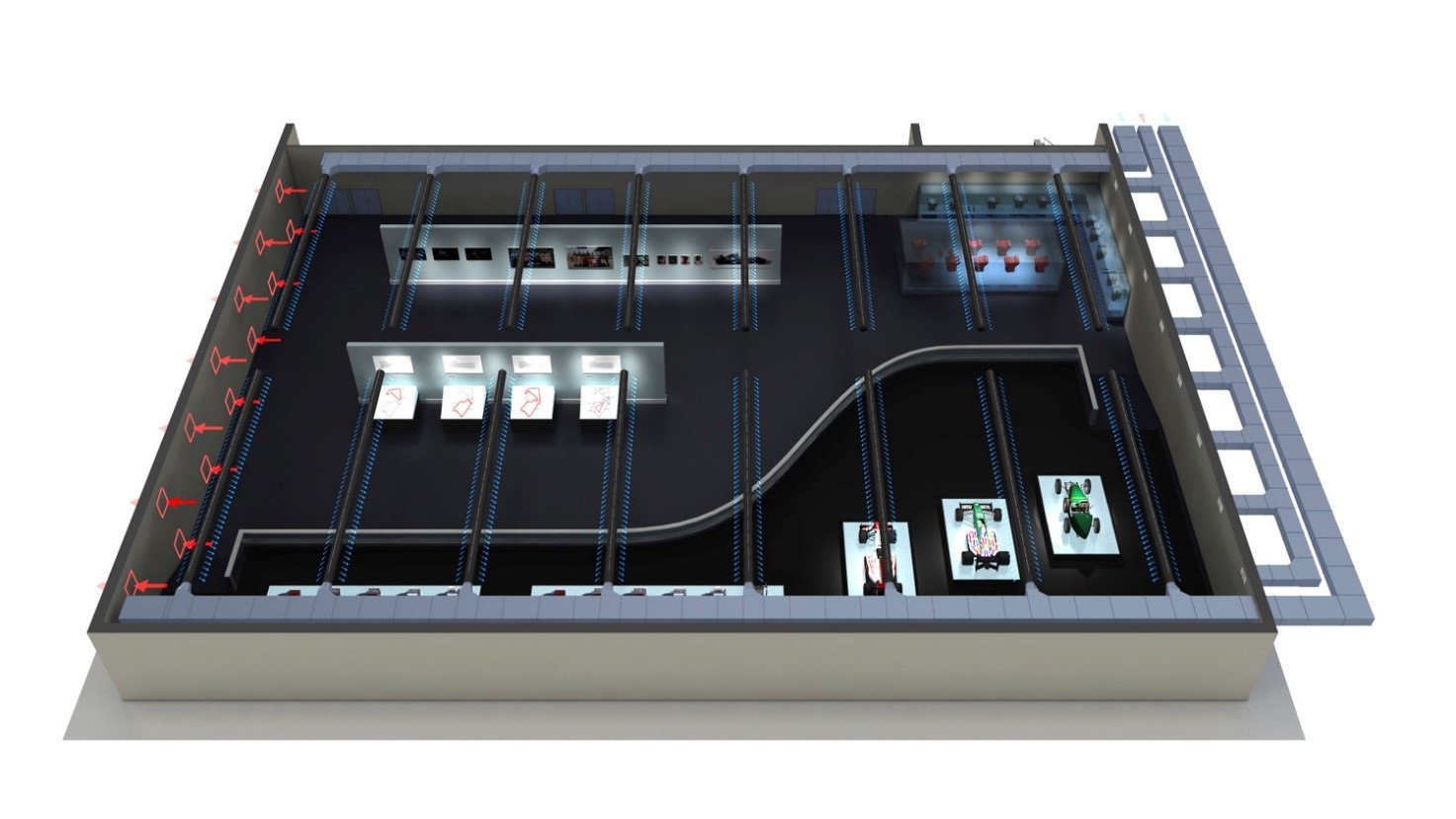

Silverstone Heritage Experience: model to demonstrate high-level ventilation to exhibition space via fabric duct and sidewall transfer grilles.

Brought to life

Through the use of computational modelling and emerging 3D-mapping technology, we can not only assess the performance of new buildings, we can fully explore them in virtual reality.

The value of these models is immense, as we can test conditions against historical measured data to see their true accuracy.

This ability to ‘play’ and scenario-test also enhances our early system-option selection process, and breaks down barriers for the engagement of the users and operators by bringing the concepts to life.

Once the model is built, it also opens up the option for further analysis, including the impact of daylight and sunlight upon the internal spaces. We can consider the exposure times and the intensity rates for individual artefacts, right up to whole collections and even entire buildings.

A great example of innovative solutions borne out of environmental modelling is The Dr Susan Weber Gallery at the V&A, Kensington (below), which displays furniture and related objects covering a 600-year span. The space utilises motorised louvres on the rooflights, with a control algorithm that considers temperature, sun position, aggregate light exposure of the internal gallery space and timeclock input. It can then make decisions about how much daylight to let into the space and when to close off the sunlight completely.

This solution, coupled with high-efficiency plant, means the conservation conditions for the furniture on display are achieved with very minimal energy input. In fact, the main energy-use comes from the district heating system that controls relative humidity fluctuations.

Passive potential

Of course, modelling analysis is not exclusive to exhibition spaces, but also for critical storage and archive areas. However, a different approach and solution is applied for these environments. Recently we’ve seen success in using Passivhaus techniques, which have traditionally been used in house building. However, the high levels of insulation, control of solar irradiance and daylight, along with exceptional air-tightness, that Passivhaus dictates allows us to maintain a constant climate condition with very minimal input.