Insights

Circularity in urban lighting: Part 2.

Who are we lighting for?

Original article published in Urban Design Journal.

In Part 1, I looked at how a lifecycle approach to lighting can reduce carbon emissions.

True circular economy.

A true circular economy is not one where we attempt to re-use as much as we can, but where nothing is wasted. When that becomes the norm then the materials in circulation will be the economy in themselves. The manufacturers of products will want to re-use instead of provide new products because the cost of new materials will be greater than those in circulation. The products in circulation will be an asset and manufacturers will provide take-back schemes to return and store products for use in future schemes. There are many steps needed to achieve this, but one of the first major steps is for the lighting industry to start playing a role not just in the products they specify but in the designs they provide.

Too often the approach to how we illuminate spaces has been to believe that we have infinite resources and that the world we live in can accept infinite amounts of light. As an industry (and this includes lighting manufacturers, design and supply companies, electricians, electrical engineers and lighting designers) we have forgotten the precious nature of the materials we specify and the light we use. A truly circular economy starts with using less product and less light. It is kinder to ecology and considers all people including those involved in the supply chains for resources. If we want to use less light, we need to consider who are we lighting for.

Who are we lighting for?

Most conversations about external lighting start with the question of ‘how much light is needed’ with the primary protagonist being the car. How much light is needed for cars to safely manoeuvre through the streets is a good question, but it is really the wrong question. However, it is understandable that this has happened; if one looks at the evolution of codes and standards, each were responding to the greater need that ran in parallel with the rise in automobiles on our roads. In 1936, the number of people killed on the roads in Great Britain was 6,502. At the time there were approximately 2.3 million motor vehicles registered in the UK. If we compare that to now, we have 41.2 million registered vehicles and 1,633 deaths. Back in 1936, the growing number of deaths was a worry, and the great minds of the lighting engineering societies focussed their attention on it with vigour, and conducted research and tests that led to the 1937: M.O.T. Departmental Committee on Street Lighting: Final Report. This report prioritised the car and its safety, with only cursory mentions of pedestrians and people, and only then about the risk of people being struck by cars.

However, by 1939 the start of the Second World War led to a change in focus for the street lighting engineering community.

The focus became how to maximise safety in a time of blackouts when all street lighting was switched off and car headlights were masked. Consideration was given to how we could manage with less light, and, like the nutritional aspects of food rationing, it was important to understand how the eye could manage in low brightness conditions, and as a result how low the illumination could be before there was a notable risk. As the end of the war approached, street lighting researchers started to think about the environments to create in the post-war world. In G H Wilson’s 1942 Street Lighting: Past, Present and Future, the authors – the Illuminating Engineering Society – dared to dream of a future world where street lighting was developed with whole towns and cities in mind, to enhance the architectural beauty of existing buildings in much the way that the redevelopment of Coventry was planned at the time.

Cannot the street lighting of the future be planned on an equally bold scale?

The notes and comments on this publication give an interesting insight into the minds of the public in relation to light. J F Colquhoun asks if after the war ‘the public would demand improvements as soon as possible afterwards because people were more light-conscious than ever before,’ suggesting that the years of being denied light had made people crave nights with an abundance of light. It is hard to genuinely appreciate the impact of no or minimal light on behaviour and psychology. Could our thirst for light have played a role in the demand for the increasing light that we see now? Could this have moved us away from what was the interesting research of the war-time scientists, ‘what is the minimum amount of light needed to comfortably see?

When we consider the question of who we light for, there is a clear and notable history that made the car and vehicular safety the primary focus for research. It is understandable because this was the imminent threat to life, but it is possible that this focus reframed the whole conversation away from the needs of people and communities. There is no doubt that our eyes can adapt to exceptionally low light levels. Walk along a country road in starlight and you can, most often, navigate very safely even though you are walking in fractions of lux (the unit of light). But when everything is illuminated, we end up layering increasing light onto the streetscape to overcome the background illumination.

Redefining our relationship with light.

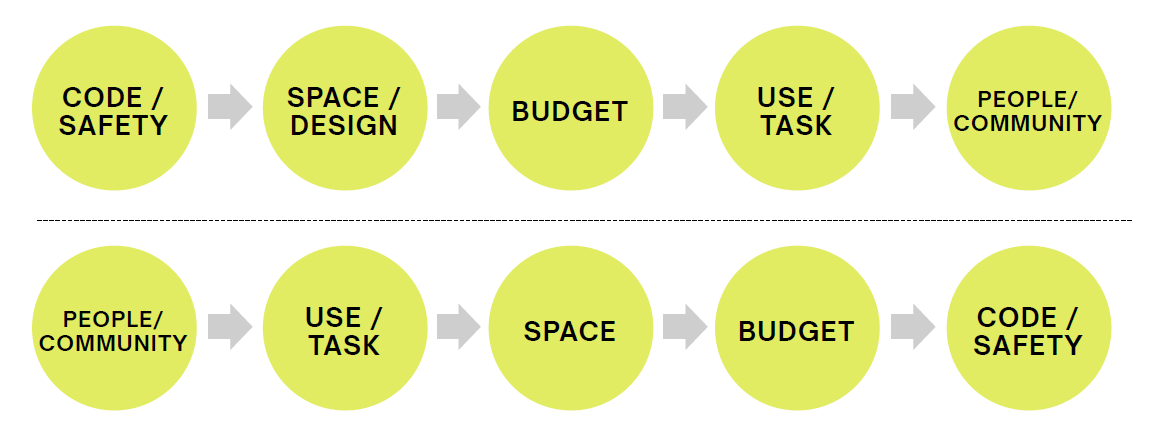

To look at the environmental impact of urban lighting and be truly circular, we need to redefine the relationship that we have with light and consider it the precious resource it is. When a project begins we start with the code and safety aspects. At some point the designer starts to think about people, with the community and social needs an afterthought. An example of this typical design process is shown. Although this may vary, the principle is the same: people are often far down the food chain of thinking. The outcome of this can be easily seen: over-illumination, ill-considered illumination and illumination focused on utility as opposed to people, communities and amenities.

We need to flip this around and put the needs of the community and people first.

What do they need? How will they use spaces? How can light be used to encourage them to use spaces? How will their needs change over time?

In doing so we may find that we need less light, which will mean less raw materials, less rare earth minerals, less power consumption, less embodied carbon and less impact on human and animal health. Reducing the amount of light we use, designing for people and communities rather than cars, and creating spaces that are considerate to ecology must be the start of the conversation, if we want to reduce the environmental impact of lighting design. It is a romantic and aspirational idea but one that will help to make great progress towards true circularity in lighting design.