Insights

Life through a lens.

Liz Bonnin.

In our latest edition of Exploare, we chatted to Liz Bonnin – a biochemist and renowned television presenter. We caught up with her about how her love for wildlife and the natural world has shaped her story. This passion remains as voracious as ever… and, today, is fuelled by a new fire – the biodiversity crisis.

Nature worked its magic on me without me even realising,” says Liz Bonnin, speaking of her childhood growing up in the mountainous region above Nice. Today, having presented more than 40 prime time programmes – from Blue Planet Live and Galapagos to Horizon and Tomorrow’s World – it’s clear Liz has found her sweet spot… combining her early love of nature with a thriving presenting career.

There are many different routes to falling in love with the planet, but a childhood spent outdoors is arguably the one that most often seals the deal. Lots of us will recognise the early memories Liz has: “I was just always outside. My sister and I were off on adventures, exploring a wood near to our house. I remember playing out there for hours on end with our two dogs. We would see hedgehogs, spiders, birds, and we were just obsessed with the detail of them.”

Moving to Ireland at age nine further fuelled Liz’s curiosity for how living things work, leading to a fascination with biology, and subsequently chemistry, at school. “I think I wanted to understand everything – right down to the chemical equations. They explained and answered so many questions!”

Igniting imaginations.

Armed with a masters in Wild Animal Biology from the Royal Veterinary College and Zoological Society of London, Liz began to build a career in science presenting. After honing her craft in entertainment programming, it was her time on BBC One’s much-lauded Bang Goes the Theory that made her into a household name – and that Liz credits as her most transformative job.

“I had a ball on that series. I still miss it every day. We were young, naive, excited, passionate! Our incredible editor just told us all to run with our stories. It was where I learnt the creative process of storytelling and, importantly, how to communicate science to a family audience. It’s actually easier to present a science programme on BBC Four because your audience already knows quite a lot. But on BBC One you have to strip it back to basics. The natural word is beautifully complex; people think it’s the science that’s complicated – actually, it’s just our universe! Sometimes it was hard to explain how everything interlinked together, but that’s what made it the most sublime training programme for science communication I could have ever dreamed of. It taught me how to be rigorous and fearless. Every time I talk about it, I pine for it. To go back and do it again would be a dream!”

Schools, parents, and society as a whole have to find better ways to encourage girls to feel like STEM-related jobs are open to them.

The programme was often recognised for its work promoting science to the whole family, effectively ‘democratising’ it for all. Today, Liz is a passionate ambassador for initiatives that encourage children and, in particular girls, to pursue STEM careers.

“Schools, parents, and society as a whole have to find better ways to encourage girls to feel like STEM-related jobs are open to them. First and foremost, I feel fervently that children should be encouraged to do what they love, rather than what they think they should. It’s a complex topic of course, and I do think both our education system and the scientific community hasn’t paid enough attention to the biases at play when it comes to how children are encouraged – whether that’s girls or children from low-income families. So, ultimately, I’m keen to show all children that there’s a space for them in this brilliant industry – and encourage schools and employers to play their part.”

It’s clear that causes – in whatever form they take – have become a common thread weaving through Liz’s more recent projects. It’s work that hasn’t gone unnoticed. In 2018, she was awarded Honorary Fellowship of the British Science Association for her ‘outstanding contribution to engaging a broad range of audiences with science, conservation and the environment’. Probably the most high-profile example of this is the landmark BBC One documentary Drowning in Plastic, which saw Liz investigate the ocean plastic crisis across the globe. A slew of awards have recognised it as a game changer in highlighting how drastic the situation is.

“Gosh, you think you know about these things, but doing Drowning in Plastic showed me how much I wasn’t aware of,” she explains. “I had been working in nature-focused TV for a while, so I’d talked to plenty of scientists off camera, and thought I had a good awareness of how wildlife and biodiversity is being destroyed by the modern world. Yet, everything I saw and learnt during filming was shocking. It has changed me forever. I’ve always had a fire in my belly to help the natural world, but after that job, there’s just no turning back for me.”

It has changed me forever. I’ve always had a fire in my belly to help the natural world, but after that job, there’s just no turning back for me.

Out of the comfort zone.

So what has Liz found the hardest aspect of her newfound role as a champion for change? “I’m a scientist, so I don’t know very much about economics. Yet you can’t talk about environmental issues without talking about politics. I’m trying to inform myself in that area, but I won’t lie – it’s really giving me a headache! Thank goodness many of the world’s economists are pushing for our economic model to become more circular. The idea of having an eco-system of resource-use between industries really gives me hope.

“Probably the toughest aspect though, is feeling like things aren’t changing fast enough. There has been some amazing work done, but just not enough when you consider the scale of the issue. When we look at the plastic crisis, it’s still business as usual for the chemical industry – production is on the increase. It’s also important to remember that everything is connected: the industry is ultimately the fossil fuel industry, because 99 percent of our plastic is made from fossil fuels. So, plastic plays a much bigger role in the wider climate emergency than people might think.”

It also doesn’t stop there. Last year, Liz joined world-leading scientists and researchers at the first ever Plastic Health Summit in Amsterdam. Understanding how plastic might affect the human body is a relatively new area of science, but it’s a particularly potent one.

“I was asked if I’d be happy to be part of a study to identify how many toxic plastics were in my body. I had four that were on the European Chemicals Agency’s ‘substances of very high concern’ list. The whole situation – both the affect on our human health and the planet itself – gives me a lot of sleepless nights. Of course, it’s important we continue to raise awareness of these issues, but I also want to do more programmes that inspire and provide hope. I know many of my friends have children who are becoming so anxious and overwhelmed about the situation so it’s vital we start to focus on solutions. There’s reason to have realistic, tangible hope.”

So what is it that keeps Liz optimistic in the face of all this? “Talking to people in the climate movement, it’s clear that there’s so much opportunity when we come together and work as a global community. An aspect of this that really pleases me is how scientists are acknowledging the value of indigenous and local knowledge. There’s a fabulous Brazilian climate scientist called Antonia Nobre. He’s worked for more than 30 years to understand how important the Amazon rainforest is, using computer models and other technology. He finally discovered that the trees are not just the lungs of the planet, but are also the circulatory system. Each and every tree draws up 1,000 litres a day in the form of mist, helping to regulate our climate and creating weather patterns the world over. Amazing stuff, right?

“…Then, after all of this work, he speaks to an indigenous Amazonian tribe who tell him they call the mist a floating river and they’ve always known the trees do that! What a perfect example of how we haven’t properly valued indigenous insight in the past – yet how invaluable it is considering the environmental crisis we’re facing. I love that the scientific process is really rigorous. You know – a study might appear in a peer-reviewed paper, but it has to be really critiqued before it can be taken as a credible idea. It’s a brilliant process and it makes sure we don’t spout nonsense or get things wrong but it’s also great to see this indigenous knowledge now being recognised as just as important as the investigative scientific way of understanding our planet.”

It’s great to see indigenous knowledge now being recognised as just as important as the investigative scientific way of understanding our planet.

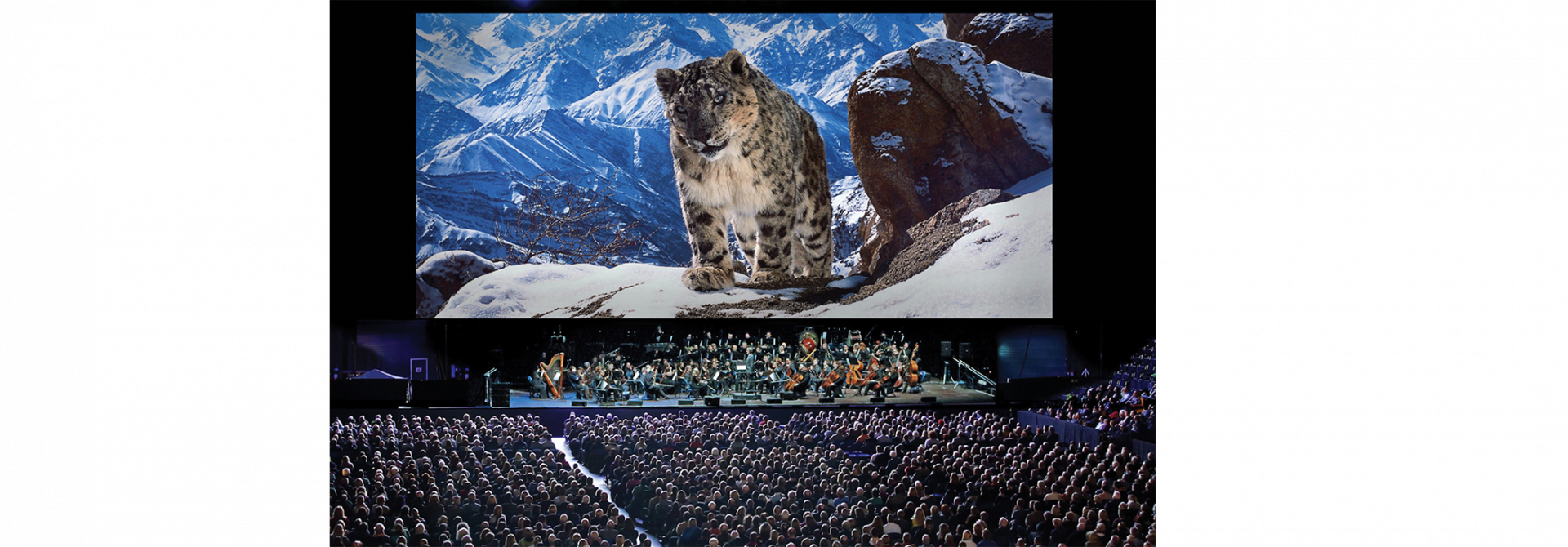

Images in this article were kindly provided by: GOAT, Alisdair Livingstone, Raw Factual Ltd, Cody Burridge, Raw TV Ltd, Andrew Crowley, Herbert Schulze and David Willis.